Yesterday The Guardian released an article citing research claiming that over 90% of REDD+ forest conservation carbon offset projects are worthless. Carbon credits from REDD+ projects are popular on Lune, so we want to respond to this article.

But first a few important points to highlight:

Firstly, we completely agree with the broader statement that most carbon offset projects are flawed and do not have the impact they claim. This is one of the biggest challenges in the carbon markets and one of the main reasons Lune exists — to help fix the carbon offset market by promoting quality and impactful projects. You can read more about how we evaluate carbon offset projects here.

Secondly, scrutiny of carbon offset projects is essential. Without it, we would never push the project developers and certification standards to improve. At least not at the pace required.

Thirdly, we need carbon offsetting and specifically forest conservation projects. Global deforestation is at an all time high (although hopefully will improve somewhat under Lula’s presidency). The single best mechanism to reduce deforestation, both planned and illegal, is to pay someone to conserve and protect nature. It just has to be done right. Quality is key.

Finally, no carbon offset project is perfect, they all have pros and cons. Proving additionality and setting accurate baselines is inherently challenging for REDD+ forest conservation projects. However, they protect some of the most important nature habitats on the planet, which store huge amounts of CO2. In addition, they often have significant co-benefits, such as biodiversity, animal protection, job opportunities, and education.

But, if you are concerned about additionality and want to optimise for this metric, we suggest funding projects such as UNDO Enhanced Weathering, Running Tide Ocean Carbon Removal, or Charm Industrial Bio-Oil Sequestration. They apply highly additional methodologies. Or alternatively, it’s increasingly popular to take a portfolio approach aligned with the Oxford Offsetting Principles, which takes into account how we should balance carbon removals with emissions avoidance and move from short term carbon storage towards durable carbon storage over time.

Response to The Guardian’s article

Having reviewed the research papers cited in The Guardian’s article, we find that the methodology applied is fundamentally flawed and does not represent the real world.

The main paper by West et. al. criticises the additionality and the baseline assumptions of Verra-certified REDD+ forest conservation projects. Additionality means the incremental impact that a project has against a “do nothing” scenario. The baseline is a forecast of the forest carbon stock in the “do nothing” scenario, ie. how much deforestation is expected. The actual carbon benefits are measured against the baseline, and the difference can be sold as carbon credits (after subtracting a buffer and assumed leakage). [Glossary]

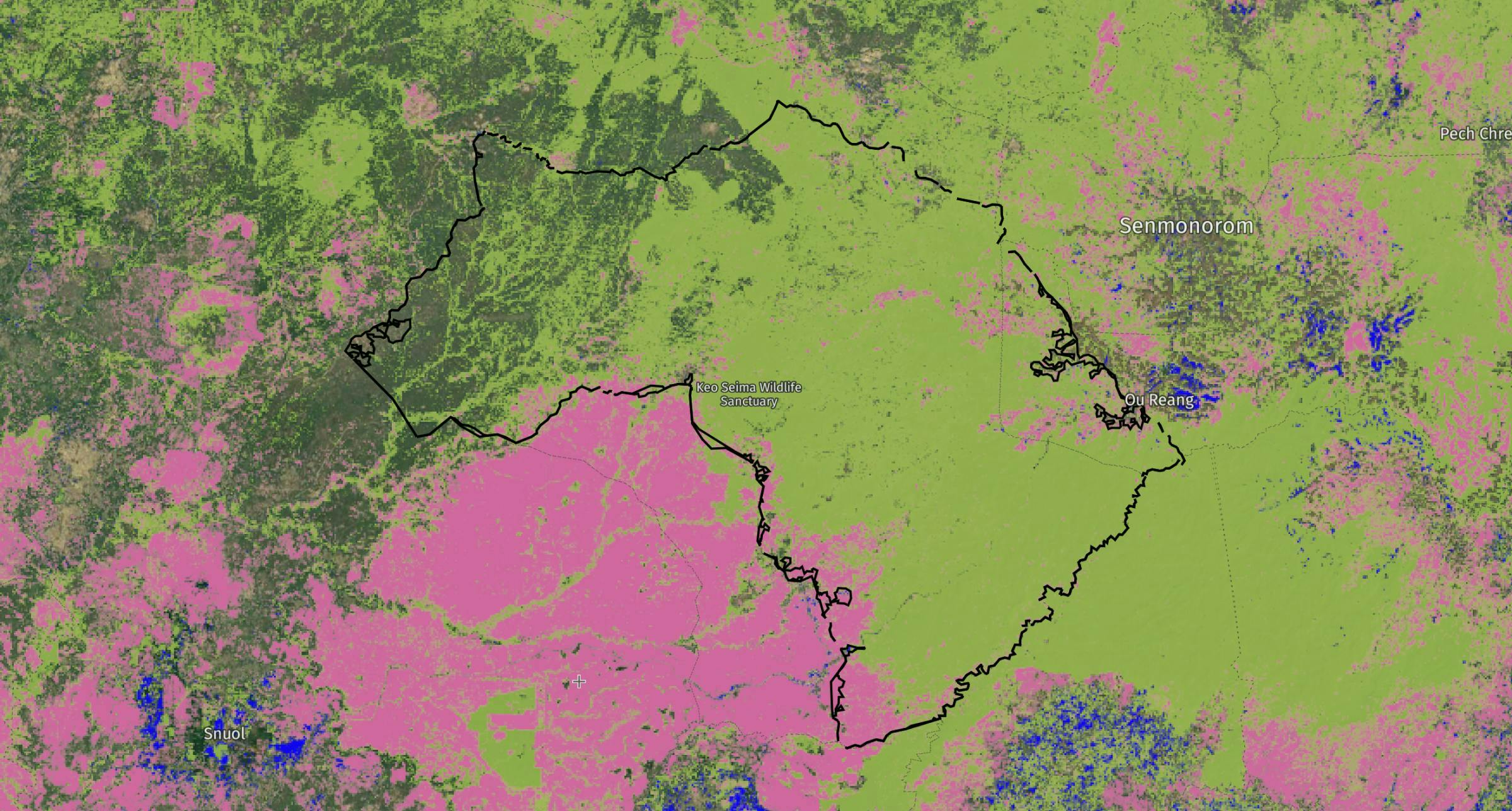

The West et. al. paper assesses the project baseline accuracy by creating a “Synthetic Control” area to compare the project baseline assumptions. The Synthetic Control area is an area that is somewhat randomly selected with some similarities to the project area, such as forest cover levels, distance to cities etc. The researchers use satellite imagery over time to compare forest coverage levels across the Synthetic Control area, the baseline assumption figures, and the actual forest coverage in the project area. However, it disregards conditions and characteristics specific to the project area. Carbon offset projects are not created on a randomly selected plot of land but rather typically in an area that has relatively high risk of deforestation; for example, is there significant deforestation in the surrounding areas that’s moving closer? The Synthetic Control areas do not take into account deforestation risks.

Why this approach is flawed:

- The Synthetic Control area is not representative of what would have happened in the project area as it does not take into account project area specific factors, such as risk of deforestation — which is one of the most important factors when designing a carbon offset project.

- Using only satellite imagery to draw a conclusion about a carbon project’s efficacy is unfortunately not enough. Carbon offset projects are complex and the images do not tell the full story.

Real example from a Lune project: if you looked at satellite imagery of the RESEX Rio Preto Jacundá project in Brazil, you would see rapid deforestation in the project area in the last few years. At first glance it might seem that this project has no impact and is, as The Guardian would call it, “worthless”. However, by engaging with the project developer we got more colour on the situation. The project was meant to issue new carbon credits early 2020 but because of Covid-restrictions was unable to complete the in-person site visits required for certification. As such, the issuance was delayed until late 2022. Almost 3 years without crucial revenue meant that the project was unable to hire enough forest guards to protect the forest and illegal loggers encroached into the project area.

Ironically, in this case, the accelerated deforestation does not highlight a flawed carbon project but it highlights the acute need for the carbon project.

The second paper cited in the Guardian article, a peer-reviewed Cambridge study, actually found that REDD+ projects do in fact lead to statistically significant reduction in deforestation and degradation by 47% and 58%, respectively. But the Guardian article fails to mention this. (Worth noting that the methodology applied in this study is also flawed. But not mentioning the result does say something about journalistic integrity.)

In summary, while we agree with the overarching message of “most carbon offset projects do not have the impact they claim”, the methodology applied in the research is fundamentally flawed and cannot be used to draw any real world conclusions.

What this means for Lune and you

Most of the projects covered in the paper have been reviewed by Lune, and we agree! They are unlikely to have the impact they claim and we filtered them out. However, our methodology is more comprehensive and includes project developer engagement, external carbon project evaluation providers, among other things. Learn more

Three of the 27 projects covered by the research are today offered by Lune. They include:

- Keo Seima in Cambodia, which according to our analysis is a great project. It is also among the top rated projects on carbon ratings platforms BeZero and Sylvera. The Guardian study does conclude that this project has had a positive impact on deforestation, although it claims the baseline is inflated. This is a result of the Synthetic Control not being representative.

- Alto Mayo in Peru, which according to our analysis is a great project. It is also among the highest rated projects on BeZero. The Guardian study’s claims are similar to Keo Seima, that the project led to reduced deforestation but had an inflated baseline.

- Concosta in Colombia, again a great project according to our analysis, which received a high rating on BeZero. The Guardian study claims no additional benefit to deforestation and an inflated baseline. However, when measuring a "confidence score" on the Synthetic Control for Conconsta, the study shows a low confidence score for this particular project.

We always welcome carbon project scrutiny and take action as needed, when new information comes to light. For example, last year when CarbonPlan criticised project developer NCX’s ton-year accounting method, we dug deeper into the subject and decided to remove NCX from the Lune platform. NCX has since been conducting more research on the subject and we might add the project back in the future, if the latest science backs the approach.

In this case, we do not consider that The Guardian’s findings require any further action on our part. We will continue evaluating carbon projects according to our robust methodology and we will continue offering a curated list of high-quality carbon projects.

If you have any questions or comments, feel free to reach out. I am always happy to discuss this matter in more depth!

Best,

Erik Stadigh

CEO, Lune

Readers also liked

Readers also liked

Subscribe for emissions intelligence insights

Get the latest updates in the world of carbon tracking, accounting, reporting, and offsetting direct to your inbox.