Avoiding double counting is crucial in credible carbon offsetting.

It’s one of the key markers in what makes a high-quality carbon offset project – alongside avoiding overestimation of impact, additionality, permanence, and co-benefits beyond carbon.

And high-quality carbon projects are a must in offsetting.

Why? Well, the question of ‘does carbon offsetting actually work’ is one that comes up a lot. And the answer is yes, but only if offsetting is done via buying carbon credits from these high-quality projects. It’s the only way you can be confident that real, lasting positive impact is being made.

So, double counting – and how to avoid it – is important to understand if you’re buying offsets.

In this article we cover:

- What is double counting in carbon offsetting?

- How do high-quality carbon projects avoid double counting? This includes an explanation of the role of carbon standards and registries.

- Examples of high-quality projects bringing radical transparency to the process of issuing carbon credits: Charm Industrial and UNDO.

What is double counting in carbon offsetting?

In the simplest terms possible, double counting is what it sounds like – counting twice.

In carbon offsetting, then, double counting refers to when a carbon credit (and the climate impact it represents) is claimed by more than one entity.

That could be because two entities are claiming the same credit (often this happens due to country level carbon trading), or because the credit is issued multiple times by the issuer (either by accident/error or for financial gain) – we’ll explore the different types of double counting in the voluntary carbon market in a moment.

Of course, if a carbon credit is claimed by more than one entity then this has huge implications for the carbon benefit made. A business could be buying 100 carbon credits to offset their carbon emissions for the year, but if those credits have already been claimed and accounted for elsewhere, their offsetting is actually having no impact.

You’ll also hear the opposite term being used – single counting.

Single counting means that a carbon credit has only been bought and claimed by one entity. This is how it should always be, as it means that the carbon benefit which the credit represents (1 carbon credit = 1 tCO2 avoided or removed) is accurate.

Let’s go back to those different types of double counting – claiming, issuing, counting.

Double claiming

Double claiming is when two entities count the same carbon credit towards their emissions reductions goals – typically a business and a country/government.

This is a particular problem with carbon trading between countries, wherein both the country buying carbon and the country selling it (i.e. a host country of a carbon project) include the emissions in their emissions calculations, leading to false carbon accounting.

Double claiming is highlighted within Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement (which governs how country to country carbon trading works) for exactly this reason. The Article makes ‘corresponding adjustments’ a requirement to ensure double counting doesn’t occur – making it necessary for both buying and selling countries to document the trade and the corresponding change made to their carbon accounting, like you would see in a bank transfer.

This can also be an issue within carbon offsetting and the Voluntary Carbon Market.

Instead of two countries, it’s typically:

- A business claiming responsibility for an amount of carbon emissions avoided/removed through buying carbon credits from a project to offset their emissions

- The host country of the carbon project which issued carbon credits claiming the same emissions avoided/removed as part of their country level carbon trading, as they work to meet climate targets.

Subscribe for the latest insights into driving climate positivity

Double issuing

Double issuing is when more than one carbon credit is issued to represent the same carbon benefit i.e. tonne of emissions avoided or removed.

This can be accidental – an error within the process of issuing and tracking carbon credits results in a credit being issued multiple times.

Or, it could be deliberate – a dodgy project developer issuing the same carbon credit multiple times to gain financially.

Double using

Double using is when the same one issued carbon credit is used twice e.g. it is duplicated within a registry, and so can be sold and used more than one.

Like double issuing, this can be accidental or deliberate for financial gain.

In all instances, this is a big red flag for the quality of the carbon project.

Either there are issues with the processes by which carbon credits are issued, tracked, and sold, which puts the real world impact of the carbon credits at question.

Or the project developer cannot be trusted.

In all instances, a company offsetting via these carbon credits is actually making no real world impact – the planet is losing out, and they are at major risk of being called out for greenwashing.

The key takeaway? Businesses must have an exclusive claim to a carbon credit for it to be truly impactful.

So how do we ensure that’s the case? Let’s take a look at how high-quality carbon projects avoid double counting.

How do high-quality carbon projects avoid double counting?

Project developers who are financing their project through the sale of carbon credits have a responsibility to make sure that the credits they sell are not being double counted.

They do that by:

- During project design and development, they should determining whether the country that the carbon project is being hosted in is engaging in carbon trading at a country level for their emission reductions targets. If it is, they also need to determine how the government is measuring and reporting the emissions reduced or removed by projects in their jurisdiction, and if this impacts the project and how it issues carbon credits for sale.

- Building transparency into voluntary carbon markets through the process of issuing, selling, and retiring carbon credits for the project – if a carbon credit can easily be tracked throughout this process, with proof of purchase and retirement on behalf of the buyer publically available, it’s easy to tell whether double issuing is taking place.

But how do carbon buyers know which projects are actually doing this due diligence – what should they be looking out for when evaluating the quality of carbon projects in relation to double counting?

What carbon buyers should look out for when evaluating carbon projects for double counting

In terms of what carbon buyers can look for to find the projects ensuring that double counting cannot take place in their project, there are two sides to it:

- Preventing double claiming: evidence of due diligence around country level emissions reductions targets

- Preventing double issuing: visibility and tracking throughout the process of issuing, selling, and retiring carbon credits.

For projects certified via a carbon standard (like Verra, Gold Standard, American Carbon Registry, Puro.Earth etc), both of these will be done through the carbon standard’s process.

Carbon projects types which cannot yet be certified via a carbon standard (i.e. early-stage techniques such as enhanced weathering, direct air capture, bio-oil sequestration which do not yet have standards set), should demonstrate how they are managing these things themselves.

Let’s take a closer look at both aspects.

Evidence of due diligence around country level double claiming

If a carbon project has been verified by a carbon standard, double counting should have been taken into account in their verification process, with checks to ensure double counting can’t take place. This information will then be publicly available via the documentation created through the verification process, giving confidence to carbon buyers.

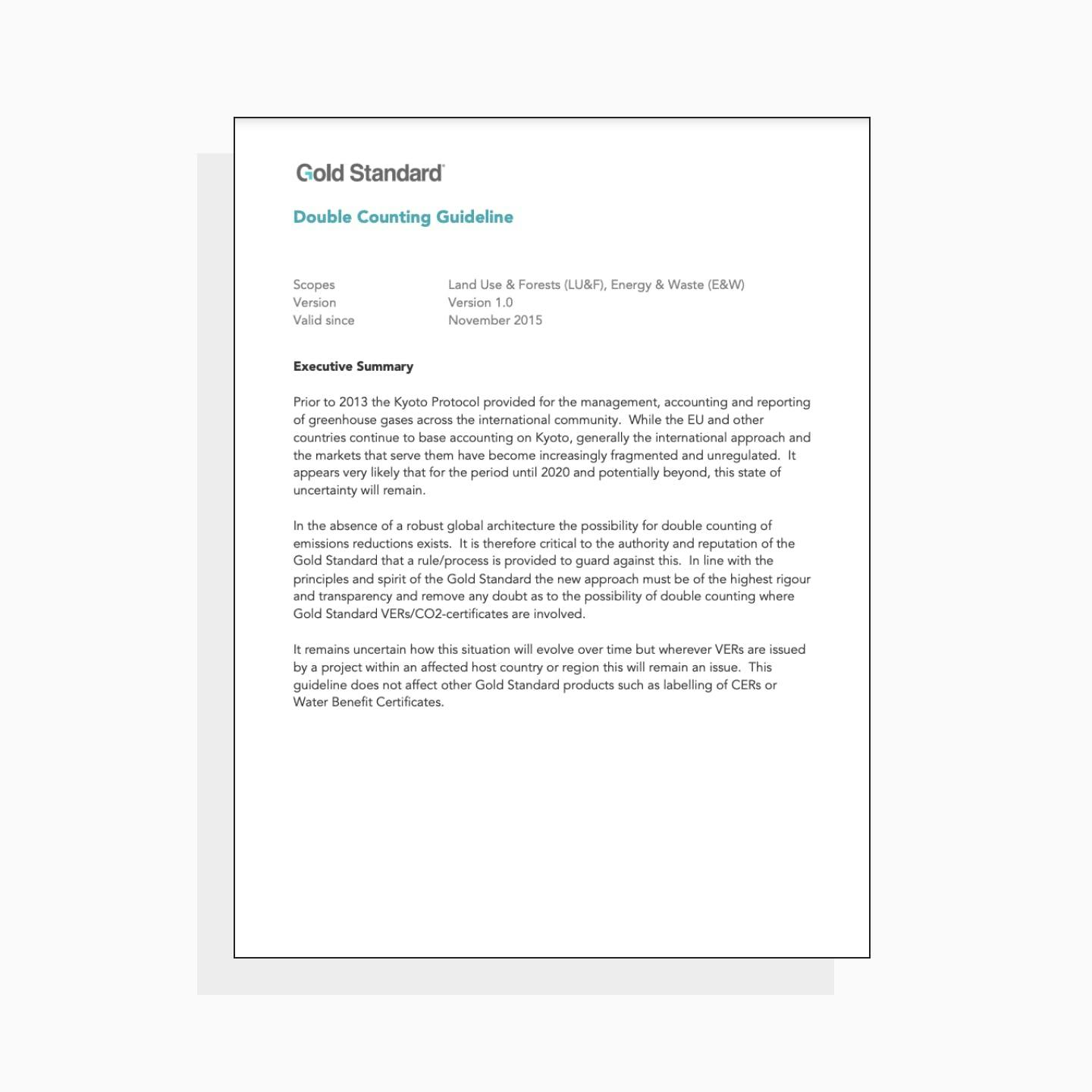

For example, Gold Standard has set guidelines on double counting, which stipulate that whilst they are verifying carbon projects they must:

- Identify whether the project is hosted by a country where there may be a risk of double claiming.

- If it is, the Project Developer must submit evidence to demonstrate why their carbon credit issuance isn’t at risk, or to demonstrate that they can cancel units within the country’s accounting mechanism.

For carbon projects which cannot yet be certified via a carbon standard there should be evidence that the developer is undergoing this due diligence themselves. In these cases, transparency is key – the information about their process for ensuring double claiming is not an issue should be easily available via their website or documentation, and they should be happy to engage and answer any questions.

Visibility and tracking throughout the process of issuing, selling, and retiring carbon credits to double counting

In terms of avoiding double issuing, wherein a single carbon credit is issued to multiple buyers (accidentally or deliberately), it’s crucial that it’s easy to track carbon credits from being issued, through to being purchased, and their eventual retirement – this transparency and visibility ensures that it’s easy to identify if double issuing is taking place.

First, a quick overview of the carbon credit process for context:

1. Issuing: carbon credits are issued for a project based on the amount of carbon they will avoid or remove, with 1 credit equal to 1tCO2.

2. Selling: carbon credits are sold by the project developers – either directly to individuals or businesses, or to middlemen like carbon marketplaces or consultancies who sell them on to individuals/businesses.

3. Proof of sale: a carbon offset certificate is issued to the beneficiary of the carbon credits – the individual or company buying the credits. This should prove that they are the single owner of the carbon credit and the climate impact it represents.

4. Retiring: the carbon credit is retired to indicate that it has been used. This only takes place once the impact that the credit represents has actually taken place. Because of this, there are a few different types of carbon credits and timelines for retirement which you’ll come across:

- Ex-post carbon credits: represent emissions avoidance or carbon removal which has already taken place. In this case retirement should be able to happen immediately (typically days to weeks).

- Ex-ante carbon credits: represent carbon removal or emissions avoidance that will take place in the future. Often these are issued at the point when the project’s work begins e.g. rock is spread in an enhanced weathering project, and the process of carbon removal begins. In this case retirement will take place in the future, once the carbon benefit has actually taken place and the credit becomes ex-post.

- Pre-purchase carbon credits: credits that are sold today but are not yet actually issued. Early-stage projects do this in order to finance their development, with a promise that the credit will be issued and retired in the future once the project is running and carbon benefit is taking place.

For more detail on these types of carbon credits and their pros and cons, head to our article on the difference between ex-post, ex-ante, and pre-purchase carbon credits.

If a project is certified via a carbon standard, then this entire process should take place through the registry of the carbon standard – credits are issued, tracked, sold, attributed to the buyer, and retired through the registry, with open and accessible documentation of the whole lifecycle. This gives carbon buyers confidence that the carbon credits issued are single counted.

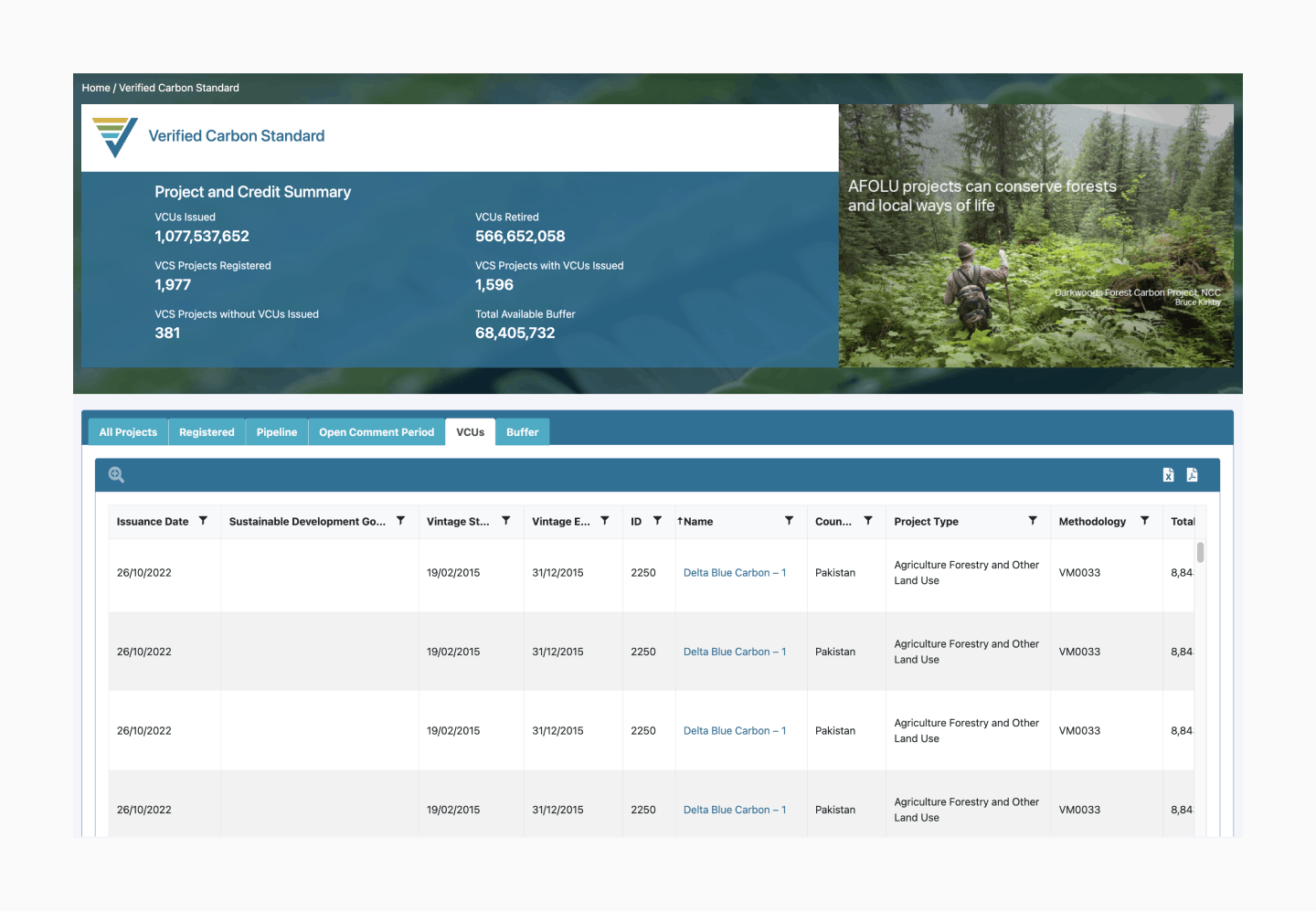

For example, the Verra registry, which is publicly available and lists all carbon credits issued for projects certified by Verra.

For instance, let’s take a look at the Delta Blue Carbon project – a mangrove restoration project in Pakistan, which is included in the Lune library of high-quality carbon projects.

Delta Blue Carbon has been verified by Verra through their Verified Carbon Standard.

This means it’s listed in the Verra registry, and you can easily see all the carbon credits issued for the project, including those which have been sold to specific buyers and if/when they are retired.

If a project is not yet certified they won't have visibility in this way through the carbon standard and registry they work with.

So, they need to demonstrate that they have oversight and control over this process themselves, monitoring at every stage to ensure double issuing can never occur.

As with the previous point, transparency is everything – a high-quality project will have open, transparent communication about their process for issuing, tracking, selling, and retiring carbon credits themselves – if they don’t have this, it’s a red flag 🚩 🚩 🚩

Let’s take a look at how two high-quality, uncertified carbon projects approach this:

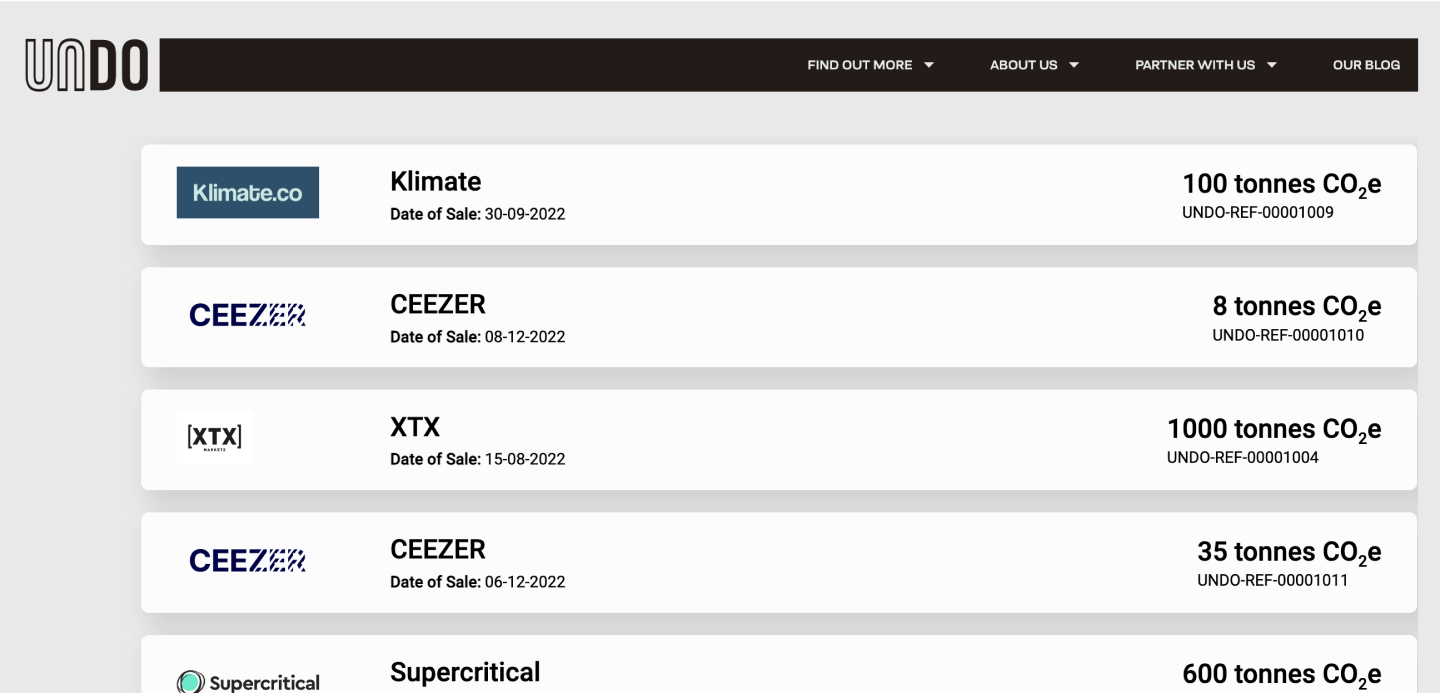

- UNDO 🪨: UNDO is an enhanced weathering project based in the UK. They manage their own registry which documents the issuance, sale, and retirement of their carbon credits. They issue ex-ante carbon credits which each have a unique serial number attached along with a schedule for when the credit will switch to ex-post i.e when the carbon removal will actually take place – and an independent auditor checks and approves this, giving an extra level of assurance that no double counting is taking place.

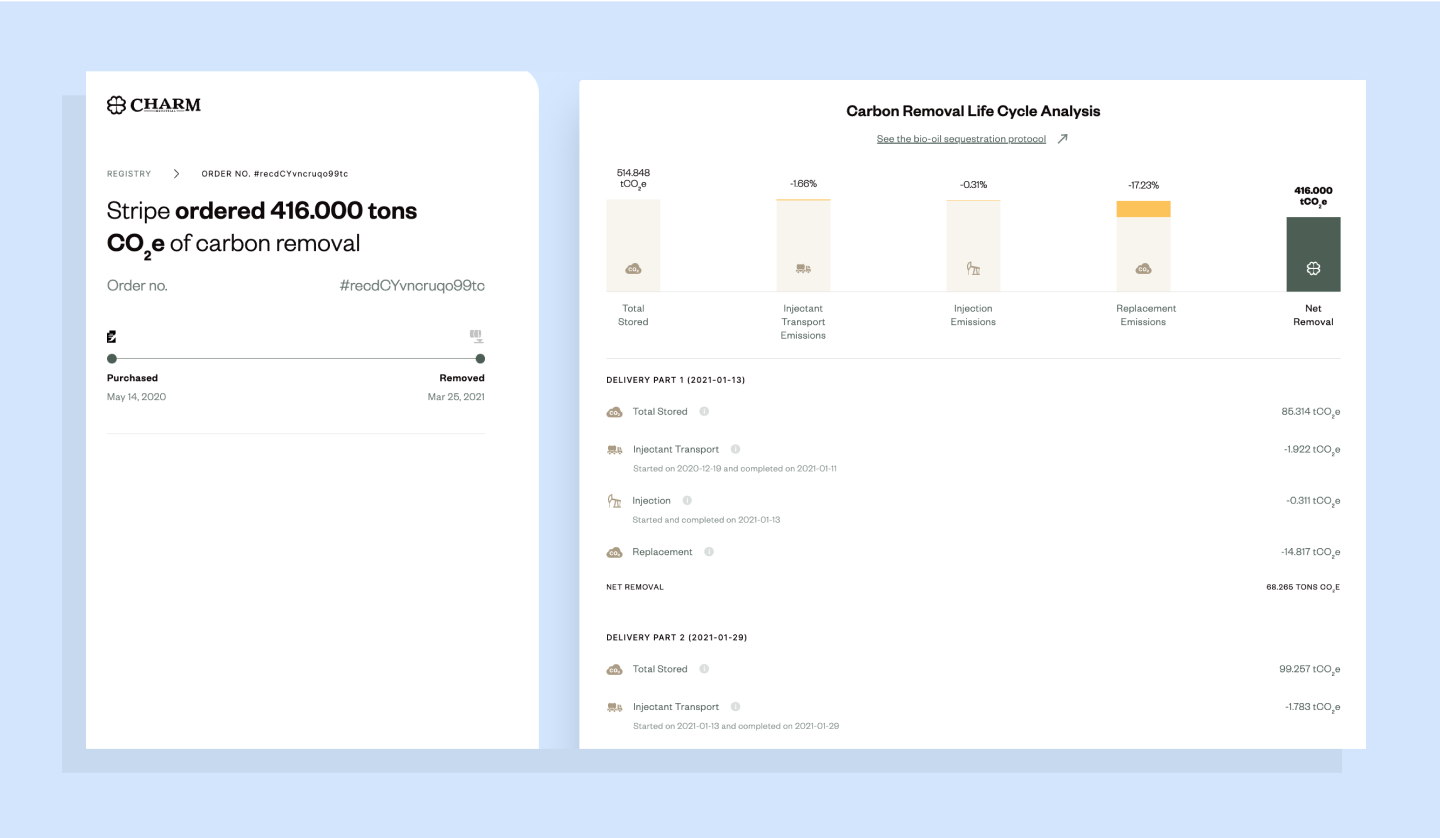

- Charm Industrial 🛢️: Charm Industrial is a bio-oil sequestration project. Like UNDO, they also manage their own registry, which includes detailed life cycle analysis for every purchase of their ex-ante carbon credits made, showing exactly where that purchase is in the process of being bought and retired – open and publicly accessible to all.

To conclude – our advice on evaluating carbon offset projects for double counting

So, in summary, to avoid double counting, carbon buyers should look out for the below when evaluating voluntary carbon market projects:

- Certification via a respected carbon standard, or

- Clear and accessible information regarding the project developer’s own process and methodology for a) conducting due diligence on country level emissions reduction targets and b) issuing, selling, attributing, and retiring carbon credits.

Projects that don’t have one or other of these, are best avoided 👋

We know this is a lot to take on – evaluating the quality of carbon projects isn’t easy. But it is crucial to ensure real impact is made through your carbon offsetting.

If you’re concerned about making the wrong choice we’d highly recommend working with a sustainability partner that has an established methodology for evaluating project quality and can help you choose the right carbon offsets – and keep track of those purchases openly.

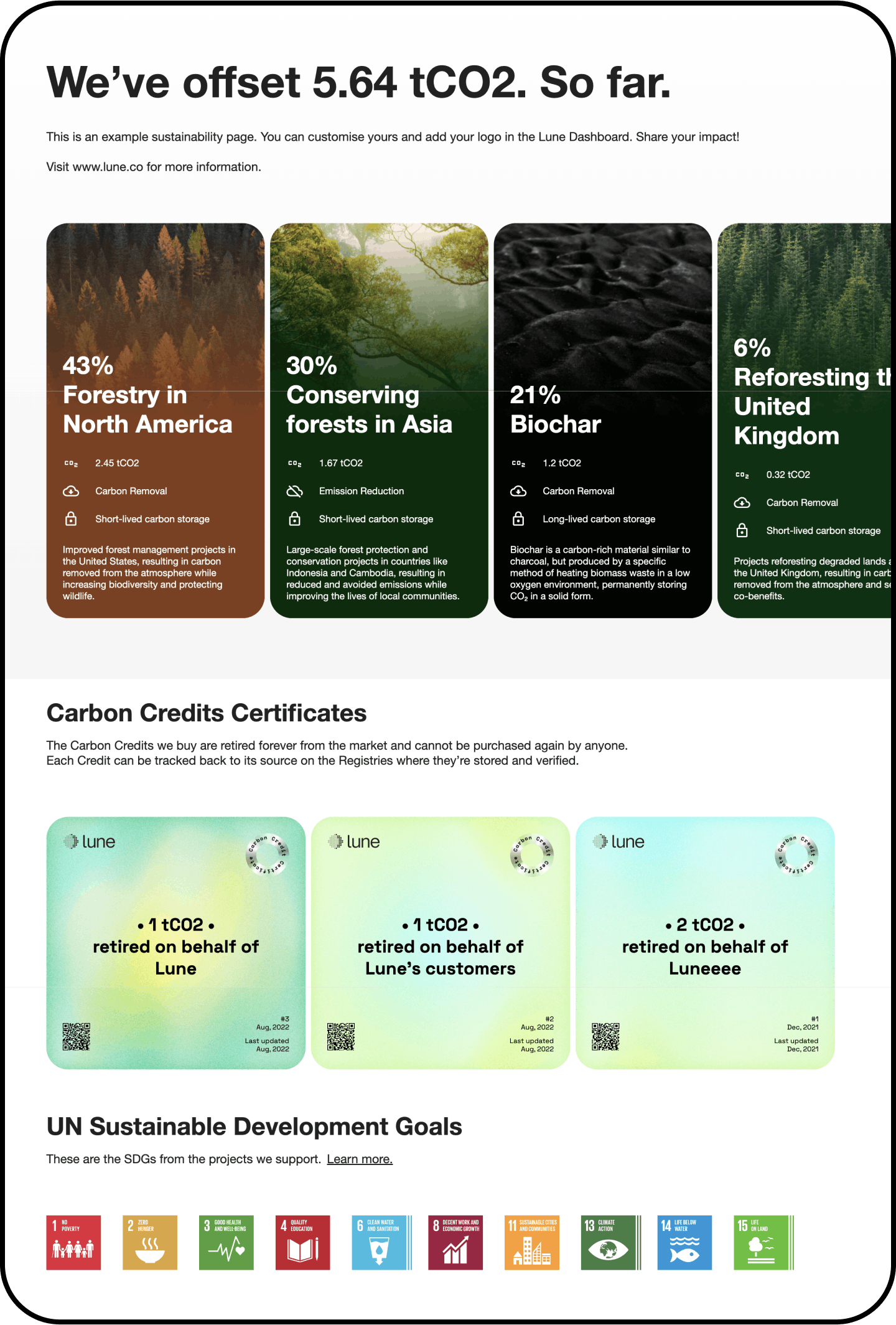

As a starting point, take a look at how we evaluate carbon projects at Lune and explore our example Lune Sustainability Page to see how we help carbon buyers create an open record of their carbon purchases.

Readers also liked

Readers also liked

Subscribe for emissions intelligence insights

Get the latest updates in the world of carbon tracking, accounting, reporting, and offsetting direct to your inbox.